I knew about conflict diamonds (diamonds mined in a war zone and sold, usually clandestinely, in order to finance an insurgent or invading army's war efforts). Several groups, including the United Nations and Amnesty International have decried the sale of conflict diamonds, arguing that their trade finances armies in fighting against legitimate governments, perpetrating human rights abuses, and prolonging devastating wars.

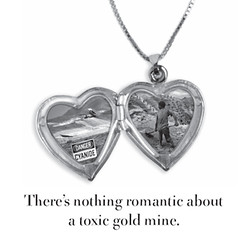

I knew about conflict diamonds (diamonds mined in a war zone and sold, usually clandestinely, in order to finance an insurgent or invading army's war efforts). Several groups, including the United Nations and Amnesty International have decried the sale of conflict diamonds, arguing that their trade finances armies in fighting against legitimate governments, perpetrating human rights abuses, and prolonging devastating wars.But "dirty gold" is a new concept for me.

Gold mining can also be enormously damaging to local communities, polluting water and land, displacing people and jobs, and leaving mountains of toxic waste for future generations to endure. Because most of the known gold deposits in the world are in microscopic form huge industrial open-pit mines, usually using cyanide to retrieve the metal from base rock, are required to make mining economically viable. And because the grades of ore are so weak, the process is hugely destructive and wasteful, with at least 30 tons of waste rock often needed to produce a single gold ring.I make deliberate choices about what I buy and believe my wallet is the most powerful tool I have for impacting the world. After considering the social and environmental costs of industrial gold mining, I'm going to ask more questions the next time I buy jewelry. And it looks like that will be easier to do, with the "No Dirty Gold" campaign now in place.

With This Ethical Ring I Thee Wed

In the last few years, as the outsize environmental impact of gold mining has been exposed, jewelers — as the retail face of the industry — have been trying to inoculate themselves against a consumer backlash. It is not here yet, but many people say it is sure to come.

In February eight jewelry companies — some small like Leber, others giant like Zales, the nation's second largest gold retailer after Wal-Mart — signed on to a national campaign called "No Dirty Gold." The campaign was created two years ago by a coalition of advocacy groups to highlight the issues surrounding gold and gold mining.

The pledge is minimal in its requirements, essentially a promise to work toward a resolution of gold's tangled issues, rather than a solution. But many environmentalists and industry officials say that the momentum and commitment are what matters.

"It's like the lock has been picked, opening a door that could lead to responsibly sourced gold," said Stephen D'Esposito, the president and executive director of Earthworks, a mining watchdog group in Washington that helped create the campaign. The eight companies together represent $6.3 billion in retail jewelry sales, or 14 percent of sales in the United States, according to Oxfam International, a confederation of groups that work on poverty and economic justice, and a leader of the campaign.

Along with Zale and Leber, the other signers are: the Signet Group (the parent firm of Sterling and Kay Jewelers), Helzberg Diamonds, Fortunoff, Cartier, Piaget and Van Cleef & Arpels. As recently as last year only Tiffany & Company had signed the "No Dirty Gold" pledge.

Most jewelers, including Mr. Leber, say that making jewelry of recycled gold is only a tiny piece of the answer. The deeper question, they say, lies around the phrase "responsible mining," and whether it is possible. About 80 percent of all the gold mined today is fabricated into jewelry.

"What does indeed constitute a responsible mining operation?" asked Michael J. Kowalski, the chairman and chief executive of Tiffany. "Who's there at the moment, and how do we get to where we need to be? The critical next step is reaching a substantive agreement on those questions."

Tiffany buys most of its gold from a Utah mine called Bingham Canyon that does not use cyanide, which can pollute water and lead to the release of other pollutants like mercury. Last year Tiffany began processing its gold itself at a plant in Rhode Island as part of a strategy to control the supply chain. Tiffany aims ultimately to provide customers with a "chain of custody assurance" stating where the gold in a ring or necklace has been, from mine to display case.

These changes are partly coming about, people in and out of the jewelry industry say, because gold mining's environmental and social impacts have become impossible to ignore, especially in developing countries where political protests, corruption and displacement of indigenous peoples have often accompanied mining.

Because most of the known gold deposits in the world are in microscopic form — the shiny nuggets of old are as dated as the miner and his mule — huge industrial open-pit mines, usually using cyanide to retrieve the metal from base rock, are required to make mining economically viable. And because the grades of ore are so weak, the process is hugely destructive and wasteful, with at least 30 tons of waste rock often needed to produce a single gold ring.

A months-long investigation by The New York Times, which led to a four-part series last year called "The Cost of Gold," also raised questions about how and whether communities in developing countries consent to the mines in their midst, and whether the long-term environmental impacts in places like Nevada and Indonesia are being correctly assessed.

Then there's the Wal-Mart effect.

Wal-Mart's strategy for everything it sells, including gold, is to eliminate the middleman, buy direct from suppliers and pass the savings on to customers. Jewelers are following suit as they try to cut costs and compete. Industry experts and executives say the trend has nothing to do with ethics, but that more control of supply makes the ethics debate over dirty gold somewhat easier, because companies are already thinking more deeply about where things come from.

"The overall theme is know your vendors," said David H. Sternblitz, a vice president and the treasurer at Zale Corporation. "Make sure you know who you're dealing with."

Mining and jewelry companies are also realizing that internal codes of conduct or environmental rules are meaningless without independent verification and inspection. Insurance companies and socially conscious investment funds are also beginning to demand standards of conduct that can be assessed by outsiders.

"They want be able to credibly say, 'I am not with stupid,' " said Michael Rae, the president of the Council for Responsible Jewellery Practices, a group formed last year by retailers and mining companies. "To avoid being judged by the lowest common denominator of the industry, they need a means by which they can differentiate their practices."

Companies like greenKarat.com, a Web-based business in Texas, and Seraglia couture in London are also proselytizing the virtues of so-called ethical jewelry.

But even if responsible, ethical mining is possible, verifying it will be difficult even with the best of intentions, industry experts say. Diamonds, furs and timber all look simple by comparison, because they all come in a discrete form that can be tracked by a paper trail. A specific tree produces a specific two-by-four; a diamond comes from one mine that can be found on a map.

Gold is not like that. It must be purified and smelted, amalgamated and combined into forms that jewelry makers can then use. That means many more steps on the journey from mine to display case, and no easy trail to follow.

1 commentaire:

i'm sure you've probably linked this before, but doesn't hurt to link again. http://www.buyblue.org

Enregistrer un commentaire